2,634 West Virginians lost

A pastor, a paramedic, a professor. It’s been one year since the pandemic began, cutting short their lives, as well as those of many others.

Published March 28, 2021 | By Lauren Peace, Gabriella Brown and Lucas Manfield

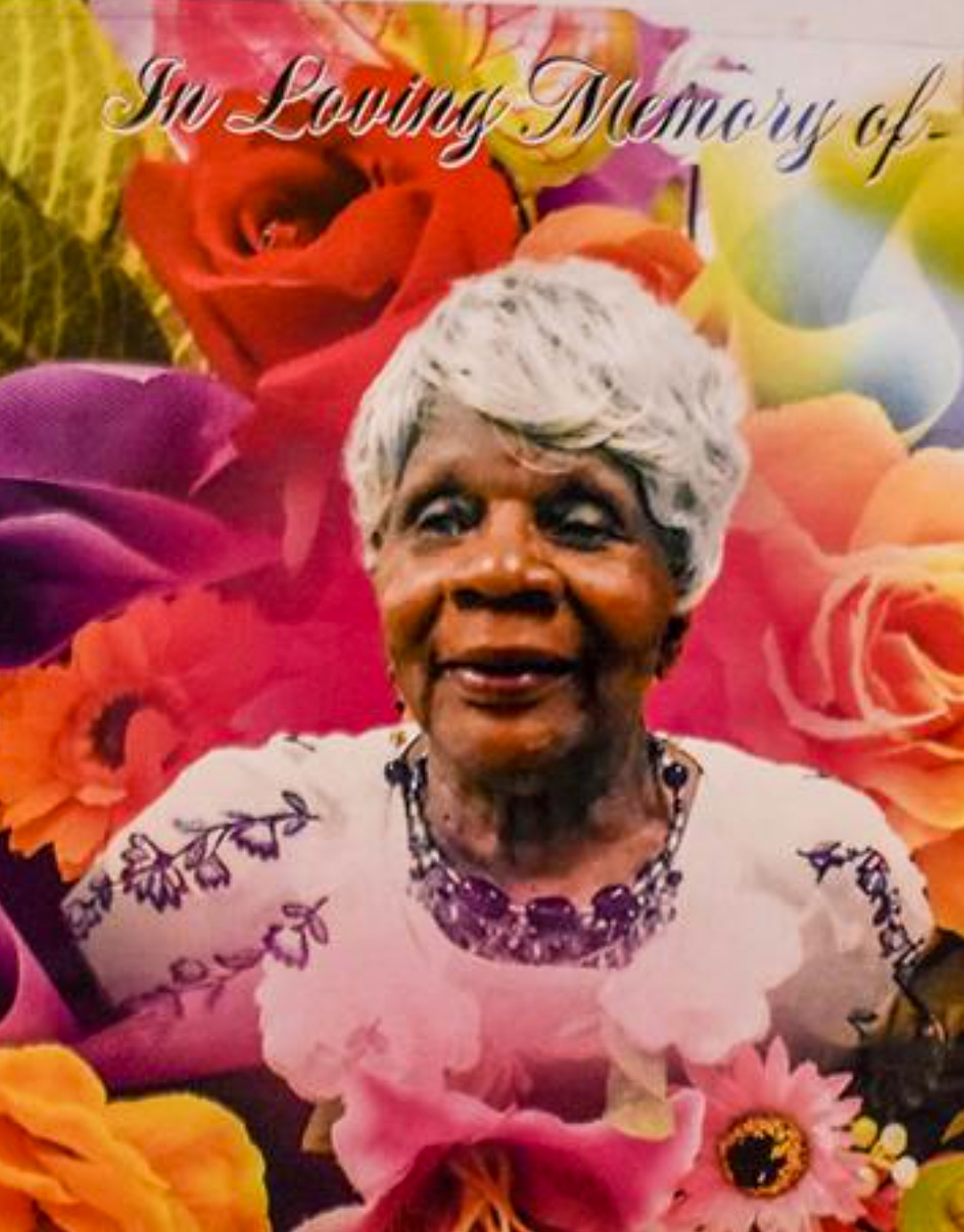

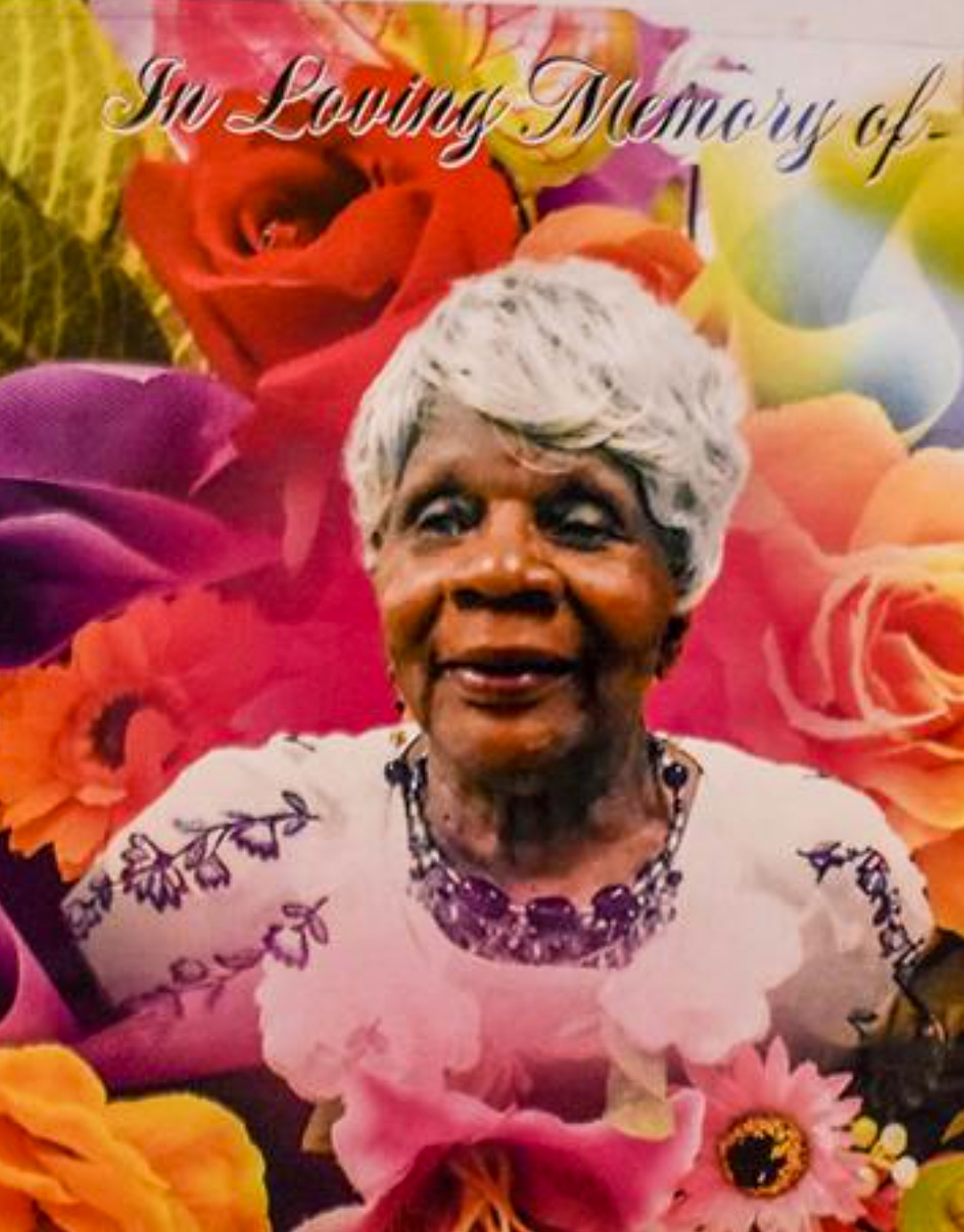

On March 29, Viola York Horton died at Ruby Memorial Hospital in Morgantown. Her death marked the first West Virginian lost to COVID-19.

The dot in the upper-left corner of your screen represents her death.

By March 28, 2021, one year later, 2,633 more Mountain State residents had died of COVID-19. State officials marked the death toll daily, in press releases and Gov. Jim Justice's briefings.

They were nameless and faceless, identified only by their age, county of residence and gender. But to their families, friends and co-workers, these West Virginians were companions, confidantes and caretakers. Each additional dot represents a West Virginian lost.

Hover over each dot for more information.

Many death notices didn't list COVID-19 as a cause, and there's no public list. But we've identified 205 of them.

Click on a dot to learn more about their lives. Tell us who we're missing.

Every night for the last 20-something years, Maxine Burgardt would call her kids and grandkids before bed and repeat the same 16 words.

“She’d call and say ‘Good night. I love you. Jesus loves you. God bless you. Sweet dreams. Say your prayers.’” said Burgardt’s granddaughter, Bridget Metheney. “We couldn’t go to bed without hearing her say that.”

Burgardt grew up on a farm near Philippi, where her parents operated a small produce stand. She married and moved to Texas, but after her first husband passed away, she returned to West Virginia, where she’d lived since 1982.

She was a homemaker and a homebody, a safe space and a security blanket for her family — including four kids, 16 grandchildren, and 17 great-grandkids.

“She was pretty much my mom,” said Metheney, who lived with Burgardt through childhood. “A lot of people would say that about her.”

Burgardt led a quiet life. After she returned from Texas, she wasn’t one to venture far beyond her home, but to the people who knew her, she was a confidante, a problem solver, the person you went to when you needed a hand.

“If somebody had trouble with a bill or couldn’t pay for something, she’d be the first person they’d call,” Metheney said. “She’d call around and work with them until the problem was solved. That was kind of her hobby.”

That, and Candy Crush.

“She loved that game,” Metheney laughed. “You could find her at the dining room table playing on her phone.”

Burgardt didn’t have serious health problems, but in March 2020, she got a fever she couldn’t kick. Her throat was sore, and she was feeling weak. Knowing that COVID-19 had entered the state, Burgardt’s family urged her to go to the local hospital. But when she got to the emergency room, they told her to go home and get some sleep.

“They didn’t even test her for the virus,” Metheney said.

Two days later, Burgardt couldn’t walk. She was too fatigued to get out of bed, but her husband got her into the car and drove her out of the county to a larger hospital, seeking help. She was taken into the emergency room in a wheelchair and diagnosed with COVID-19. She died a month later, on April 22. Burgardt was 69 years old.

“It’s hard to let it go and to feel like she wasn’t taken from us too soon,” said Metheney. “I believe that God took her for a reason, but it hurts.”

Metheney said that she wants Burgardt to be remembered for her generosity and love.

“She was kind to everybody,” Burgardt said. “She loved people with no reserve at all.”

Facing several underlying health conditions and the closure of his life-long place of employment, Daniel Brown decided to retire as a COVID-19 precaution.

Brown, an X-ray technician, worked at the Bluefield Regional Medical Center in Mercer County for decades before its permanent closure of all inpatient and ancillary services at the end of July 2020. With no children of his own, Brown often picked up shifts at the hospital every holiday to ensure his coworkers could spend time with their families. It wasn’t uncommon for him to spend his Christmas bonus on toys and gaming systems to give to children through the Salvation Army Angel Tree or Toys for Tots.

During his last few days working at the hospital, Brown left a special note and drawing for each of his co-workers.

“He drew a picture of himself kind of waving goodbye, and he has a little bubble coming out of his mouth that says ‘thanks for the memories’,” said Brandi Fain, Brown’s niece.

Beside the drawing is a quote, “If in the end we should go our separate ways, I know the lessons I learned here were worth it all.”

At the beginning of November, about four months into his retirement, Brown developed a mild cough. Soon after, he stopped answering the phone. After about three days, Fain’s mother finally reached her brother. His voice was almost unrecognizable.

“He didn’t even sound like himself,” Fain said. "My mom kept saying ‘is this Danny Brown? Is this my brother?’”

On the other end of the line, Brown was struggling to tell his sister he needed something to drink. When Fain arrived to help, she noticed newspapers and mail had been piling up on his porch for days.

“I barged in the house, and he was laying on the couch,” she said. “He was very pale and very weak. It was quite scary.”

Brown was rushed to the Princeton Community Hospital. With his oxygen levels in the upper 80% range, he was placed on a ventilator, which he would never come off of. COVID-19 precautions prevented his family from being by his side, but Brown was not alone.

Many of the people whom Brown had worked alongside his entire career had transferred to Princeton Community Hospital after Bluefield closed. Those same nurses and trusted co-workers were the ones now fighting to save his life.

Separated by the brick hospital walls, Brown’s family sat in the parking lot praying for his recovery. Inside, a nurse who Brown had always been close to placed a drawing of a heart on the hospital window to remind his family Brown was in good hands.

Brown received treatment until Dec. 3 when he passed due to complications from COVID-19. His oxygen levels had dropped into the 30% range, inflicting permanent damage to his brain and vital organs; Fain and her family had to make the difficult decision to not resuscitate him.

“Barbara, who had worked with him, went in there and held his hand and was with him until he passed,” Fain said. “We sat outside and waited, but he had a family member in there with him until he passed away.”

Before Brown retired, the drawing and quote he left at the Bluefield Medical Center were framed as a way for all to remember Brown’s kindness and willingness to give. They’ve now become an important symbol of his life.

“We used it at his funeral because it was so fitting,” Fain said. “If we should go our separate ways, which he did, then the lessons we learned here were worth it all. That was sort of his way — what he learned was worth it at all.”

When Teddy Nelson had your back, you knew that no matter what life threw your way, things were going to end up OK.

“He was like a brother to me,” said Trent Dalton, who met Nelson on the football field in first grade. “I was a quarterback and he was a linebacker. He protected me.”

Nelson loved football. He was an avid Denver Broncos fan who kept up with all the games. In high school, he struggled with health problems and couldn’t play much, but he was a valued member of the Logan High football team because he was a hard worker and selfless, the kind of person that makes everyone else better. He was someone people wanted around.

“He would give the shirt off his back to somebody in need,” Dalton said. “He was always smiling. And if things were ever not going well in his life, you wouldn’t have ever known. He didn’t let it impact how he treated you. He wanted everyone to feel good.”

Larra Elkins, one of Nelson’s closest friends, described him as a goofball. Her favorite memories of him are the simple ones — just driving around town.

“Me and him would take car rides and we’d be jamming out to Hannah Montana and ‘Baby Got Back,’ and he’d be singing,” Elkins said with a smile. “He was just full of it. He loved making people laugh.”

And although Nelson was a big guy, and could be physically intimidating if you didn’t know him, “he didn’t have a mean bone in his body,” Elkins said.

Nelson loved to fish, loved his German Shepherd, and especially loved his family.

When his grandmother passed away in March 2020, Dalton came into town from his Ohio home to be there for Nelson and his family as they grieved.

“We went out to breakfast together the day after his grandma’s funeral,” Dalton said. “That was the last time we ever spent together.”

Shortly after the funeral, Nelson got sick. At first, it felt like a common cold, but as it progressed, he decided to seek medical care. Nelson went to a MedExpress where he was told he had bronchitis.

A week later, he had trouble breathing and was admitted to the hospital. Nelson died on April 11. He was 25 years old.

“I was texting him, and he wasn’t replying to me and that’s when I found out he was on the vent and I never heard from him again,” Elkins said. “He didn’t get to live the life that he should have. He should be here. I still can’t believe that he’s gone.”

Viola York Horton loved to line dance. The 88-year-old from Fairmont was often the life of the party. Moving kept her young, gave her energy and bonded her with her daughter Brenda Kent, who taught a community dance class.

“My mother could move,” said Kent. “And people loved to watch her dance.”

Called “Ms. Vi” by friends and acquaintances, Horton was known for her tenacious spirit and commitment to her church. She was a “go-getter” who sang and traveled with her church choir for the better part of the past 40 years.

“Everywhere that choir went, my mother went,” said Kent. “She wouldn’t miss a day of singing for nothing.”

Horton spent her life in Fairmont. She lived in the same house she was born in, and raised her three children as a single mother, earning a living in housekeeping and service work.

It was hard at times, Kent said. But Horton always made sure there was food on the table and shoes on her children’s feet.

“And she never, no matter what, missed a Christmas,” Kent said. “She was the hardest worker you’d ever meet.”

In early March 2020, as COVID-19 began to spread across the United States, but before West Virginians had felt the devastation caused by the virus, Horton joined her church and six other predominantly Black congregations to celebrate the anniversary of a local reverend.

That gathering resulted in a COVID-19 outbreak that tore through the Black community in north-central West Virginia.

At first, Kent said, her mother seemed fine. But one day at a time, Horton morphed into a shell of the lively octogenarian she was. On a Friday, she complained of a minor headache. On Saturday, she didn’t want to leave the house. On Sunday, Kent decided that if her mother didn’t feel better, they’d go see the doctor on Monday.

But before they could get there, Horton collapsed in the hallway on the way to the bathroom around 4 a.m. Monday. Kent called an ambulance, which took her mother to a hospital in Morgantown. She died there a few days later; the first West Virginian officially lost to COVID-19.

“I kept telling my mother, ‘Momma you’re coming home. They’re gonna fix you.’ And she said, “I’m going home, Brenda, but I’m not coming home,’” Kent said. “I knew what she meant, but God knows I didn’t want to hear it.

“I miss my mother so much, I hate to even talk about it,” Kent said. “I’m trying to get past it, but it’s just so hard, when everything in my life was my mom.”

Charles Hiser’s life’s work was in getting food to the people of Greenbrier County.

In his younger years, it was through a small grocery store in Alderson.

“Hiser’s Superette, that’s what they called it,” said Hiser’s youngest daughter, Libby Morgan.

A lot of times, people at the store wouldn’t have the money to pay, but that didn’t matter to Hiser. He’d tell people to take what they needed and pay him back when they could.

“He couldn’t see anybody go without food,” Morgan said.

As Hiser grew older and retired, he stayed busy by collecting and passing out meals to local seniors. The senior citizens van would pick him up at his home and they’d head off to Kroger to pick up day-old bread and juice to take back and hand out to people at the senior center.

“That center was the best thing for Dad,” said Morgan. “It was just down the road from his house and he loved it there. He liked being busy. He liked working.”

Hiser, whose wife died in the early 2000s, was healthy and independent at 82 years old. He kept his house clean, but he wasn’t much of a cook, so Morgan would bring him pre-cooked meals. On Thursday’s they’d go out to eat, getting burgers or milkshakes; whatever Hiser was craving.

“That was our day,” Morgan said. “And when the pandemic started we couldn’t do that anymore. It was really hard on Dad.”

For the first few months of the pandemic, Hiser was really careful. He rarely left his home.

“We were doing everything we could to keep him safe,” Morgan said.

And at first, that included skipping out on church, where Hiser would go every Sunday. But when in-person services resumed in June, about a month after Gov. Jim Justice began reopening the state, Morgan and Hiser agreed that he could attend.

“I thought of all places, Dad would be safe at church,” Morgan said. “He loved church.”

But a week after the first service Hiser attended, congregation members started to test positive. Morgan got a call that her father needed to be tested.

“I explained to him how the test worked. He said, ‘Well you know what that means don’t you? It means if I test positive, I’m going to die sooner,’” Morgan remembered. “I said ‘Oh Dad, you always look at the negatives. It will be fine.’”

When the test came back positive, Morgan was in shock.

“I just couldn’t. I couldn’t tell him,” she said. “I couldn’t do it.”

Her husband called and told Hiser over the phone. Not long after, Hiser’s health began to go downhill. He was taken to a local hospital, where he died on June 26.

“My daddy never met a stranger. There wasn’t a person in the world who didn’t like Dad” Morgan said. “We miss him.”

The first night Lawrence “Mac” McAfee spent in Ripley, he wasn’t very impressed. He and his wife Monica had just moved up to West Virginia from his home state of Georgia, and he was used to the Atlanta buzz. Ripley, especially on a weekday at dusk, was quiet.

But not long after arriving, McAfee grew to love the Mountain State.

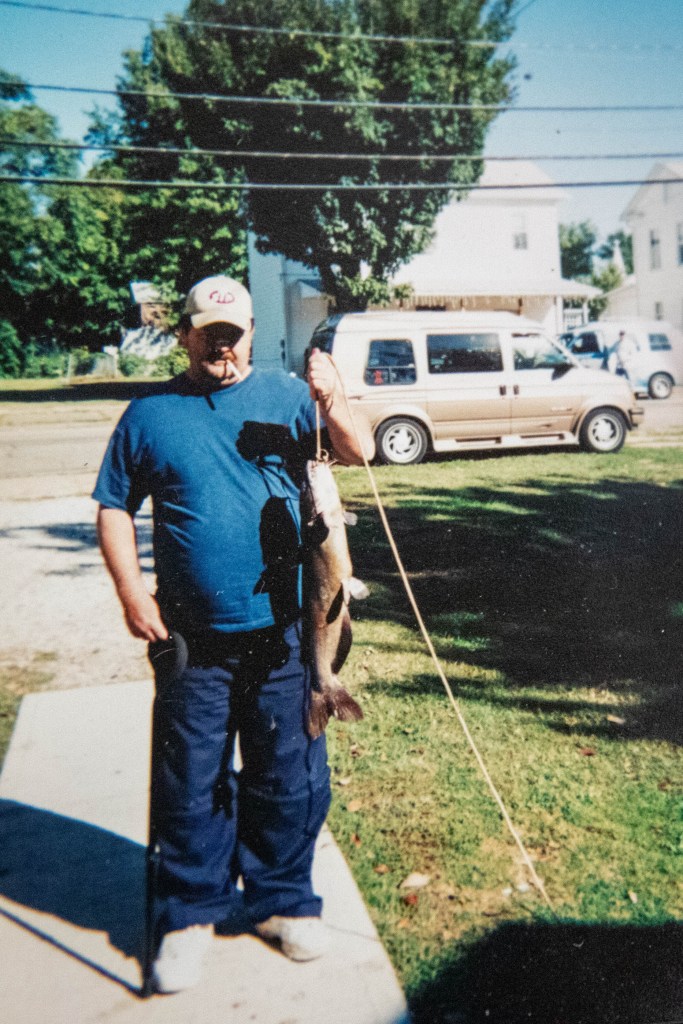

He was an avid fisher — he especially liked cat-fishing at night — and as a trained-mechanic he spent his free time tinkering with cars in the backyard.

McAfee was quiet, “a loner,” but with a dry sense of humor that kept the people around him smiling, like when he joked that he and Monica had gone on a cruise for their wedding day.

“He’d say, we cruised on up to Chattanooga,” where the couple married in a courthouse a year after they met, “and cruised right back,” Monica McAfee laughed.

Although he was reserved, McAfee was also sentimental. He promised his wife that if they made it 10 years they’d renew their vows — this time in a church.

On their 10th anniversary, that’s exactly what they did. Monica McAfee wore a white dress with half-sleeves and a pearl necklace; McAfee wore a tux with a red satin vest and bowtie to match.

But not long after, McAfee’shealth began to decline. He had overcome addiction when he was younger, but the drugs and alcohol had taken a toll on his heart and liver. He had a heart attack, followed by a stroke.

“It almost killed him. I thought we were going to lose him,” Monica McAfee said. “But he survived.”

The complications left McAfee blind and in a wheelchair. In 2015 at the age of 53, he moved into Eldercare Health and Rehabilitation, a nursing home about 13 miles southeast of the couple’s home. It was close enough for daily visits, and that made Monica McAfee feel safe.

For the next five years, she said McAfee lived happily. The couple spent time together at the home. McAfee especially loved it when his grandkids came to visit. They’d lay in bed and put Seinfeld on the television and laugh. He was happy, Monica McAfee said.

But in early April 2020, just a month after the first case of COVID-19 was reported in West Virginia, McAfee got sick. The virus had gotten into the nursing home where he lived, and 71 of the 86 residents tested positive for COVID-19.

By early May, he and 14 other residents were dead. He was 58 years old.

“People think it’s all old people in these homes,” Monica McAfee said. “It’s not. My husband was living. He was alive.”

James Vance’s first priority was spending time with his family.

That’s part of the reason he retired in June 2020, after 23 years as a Bluefield police officer, climbing the ranks from dispatcher to Lieutenant.

“With our kids being little, it was finally to the point where he thought, maybe I should retire, I'll have more time with the girls,” said Jerri Vance, James’ widow. “Luckily, this summer and then this fall, he really did.”

A father of four, Vance never passed the opportunity to see his children compete in sports competitions, even if it meant rushing over from work and showing up in his uniform. Each summer, he treated them to family vacations to places like the Bahamas and Disney World.

Despite retiring, Vance enjoyed being active and picked up a part-time job as a forklift operator. He was cautious about COVID-19, texting his wife pictures of him wearing protective equipment, and stripping off any gear and clothes in the garage before entering the house. He was concerned about contracting the virus, but bringing it into his home was his biggest fear.

“And it still happened,” Jerri Vance said. “Because we all ended up sick.”

Vance began developing a mild cough in early December, but insisted he was OK. A few days later, his wife and 12-year-old daughter began to develop mild symptoms too, and then all three tested positive for the virus. Within days, Vance’s symptoms worsened. He struggled to sleep and the exhaustion left him unmotivated. When he began vomiting frequently, he decided it was time to seek medical attention.

“He got up and showered, and that's the last time we saw him,” his wife said.

Once arriving at the hospital, doctors told Vance he had developed pneumonia. Limited bed spaces required him to transfer to Ruby Memorial Hospital in Morgantown, where health care workers said his lungs looked like blown glass. He struggled to breathe as his oxygen levels dropped, and was put on extracorporeal life support.

Despite his condition, Vance was transferred again, this time to Pittsburgh, where he spent 19 days on a ventilator. By his daughter’s birthday on Dec. 31, he had recovered enough to come off the ventilator and wish her a happy birthday.

“Jamie said, ‘Daddy, you need to come put my Barbie house together’, and he winked at her,” Jerri Vance said. “It seemed like it was the most real conversation that we had had with him in a month.”

Just two days later, she called the hospital for a routine check-in on Vance’s condition. A doctor told her Vance had taken a turn for the worst.

With a five hour drive ahead of her, Jerri Vance wasted no time, found a police escort and rushed to the hospital. Just before reaching Elkins, she learned her husband had died.

“I feel cheated that I only had 15 years with him,” Jerri Vance said. “And I feel cheated for my kids that were 12 and seven and had to grow up without a daddy.”

Following Vance’s death, his family was flooded with letters and cards filled with kind words. Many reflected on the times he had helped them and the kindness he brought to the community. Jerri Vance knew her husband was selfless, but never realized just how much he had meant to so many people.

“Everybody loved him, our entire community, the whole county, it's unreal,” she said. “ I hate that I had to find out this way how important he was to everybody.”

Bernice Powell was a lifelong West Virginian who called the Mountain State home for 95 good years.

When she was younger, Powell was known for being stylish and “very, very social.”

“She wouldn’t even go out the front door to pick up the paper without her lipstick on,” said Carla Harbour, Powell’s daughter. “She always looked good.”

And so did her home. It was spotless; perfectly organized with simple decorative touches. So when dust started to accumulate and things were left out of place, Harbour said, it was a sign that her mother was starting to fade. She began to look into nursing homes, where her mother would be cared for in her old age.

The trouble was, there weren’t many options local to Huntington. The ones with top reviews were full or expensive, and Powell didn’t want to move far.

“I began shopping around online, but there was nothing,” Harbour said. “That’s the sad thing about West Virginia. We fail our older citizens.”

For months, Powell continued to live alone in her home. Eventually she moved into Huntington Health and Rehabilitation, a for-profit nursing home that is part of a larger chain and one of the bigger facilities in the state.

COVID got into the facility in October, and the virus ravaged patients and staff throughout the home. More than 125 people tested positive, including Powell. She died on Nov. 10.

“She had survived colon cancer in her 70s, and in her 90s she was healthy,” Harbour said. “You just don’t expect something like this to be how a life ends.”

Rick Hood had been through a lot. A motorcycle accident left him with a head injury, and the former bodybuilder and football star had to relearn to walk.

“The doctors said he wasn’t going to make it, but my brother showed them otherwise,” said Wallace Hood, Rick’s older brother. “He was a miracle.”

It was a slow recovery. As Rick Hood became physically stronger, his brain was still functioning more slowly because of the injury. He had to learn to read again, to think clearly. He was different after the accident, his brother said.

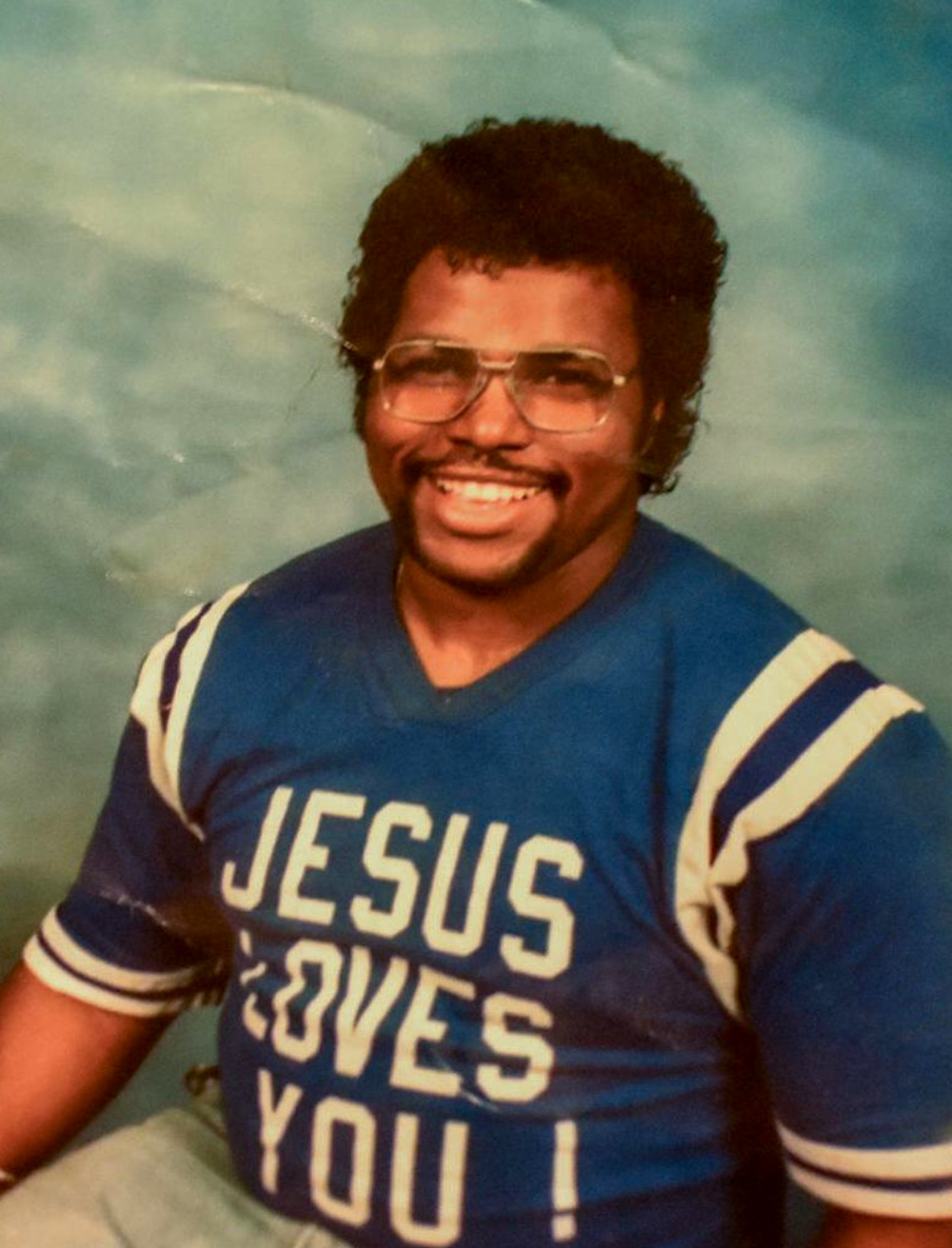

“Rick struggled mentally, as a side effect of the head injury,” he said. “But my brother was the strongest man that I knew with his faith in God.”

Rick Hood traveled to Oklahoma where he studied to become a pastor and eventually relearned to read. He returned to West Virginia as a reverend and became a fixture of his church, never missing a service. It was through a gathering in early March that Hood was exposed to COVID-19.

“He said to me before he went, ‘God will take care of me,’” said Wallace Hood. “I know he believed it.”

Rick Hood died at Ruby Memorial Hospital in Morgantown on April 10. He was 62 years old.

“It’s one thing when your family gets sick, and you go to the hospital and get to say ‘I love you mom, I love you dad, I love you cousin,’” said Wallace Hood. “But it’s different when you don’t know what’s going on. It’s different when you can’t be there.

“I want to know, what were my brother’s last words?”